Skip to main content

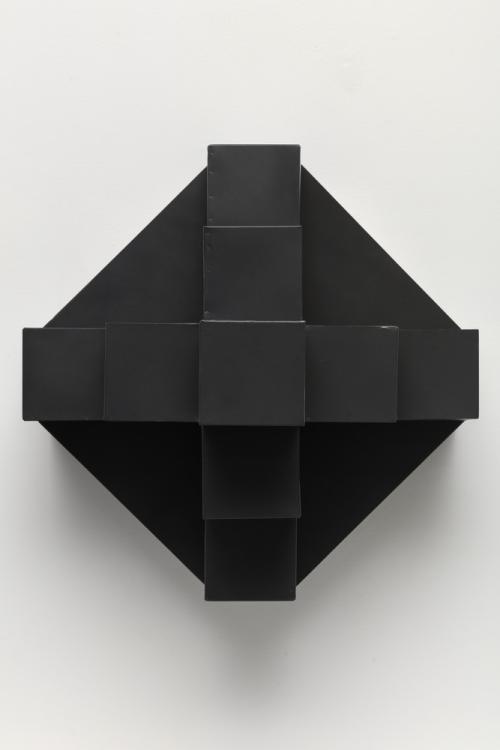

Guardian No. 4

Artist

Clyde Connell

(American, 1901-1998)

Date1988

MediumRedwood, paper, glue and metal

DimensionsOverall: 91 × 12 1/4 × 3 1/2 in. (231.14 × 31.12 × 8.89 cm)

Credit LineCollection of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Anonymous Gift

Object number1991.33

Status

Not on viewSignedverso l.l.c. "Clyde Connell"

verso l.r.c. "CC [with circle around it]/1988/Lake/Bistineau

Copyright© Estate of Clyde Connell

Category

Label TextClyde Connell experienced the patriarchal Southern culture of twentieth-century America firsthand. Born into a privileged white family, she grew up on a large plantation and lived most of her life, which spanned almost the entire twentieth century, in Louisiana. Her work stems from her personal experiences and empathy for the oppressed—particularly women and rural Southern blacks. Guardian No. 4, 1988—one of Connell’s totemic sculptures covered in abstract pictographs or hieroglyphs—exemplifies her artistic impulse to explore the social and geographical dimensions of the human condition.

Connell made Guardian No. 4 using found and natural materials from around Lake Bistineau, an isolated, swampy waterway on the outskirts of Shreveport, Louisiana, where she lived and worked for the last fifty years of her life. The surface of the piece is overlaid with simplified geometric shapes and rusted metal parts. Its support is a vertical redwood plank covered in a pulpy papier-mâché “skin” made from boiling a mixture of newspaper and glue. The vertical orientation of the work and its skinlike surface lend an anthropomorphic character while also evoking the moss-draped cypress trees that shelter the lake. The pictographs covering the form, however, suggest more multivalent meanings. The abstract images might evoke a female figure, a sentry holding a club, or a prison guard’s key ring. The work’s title indicates protection or guardianship, but who is the guard looking after and what does it protect one from?

Connell acknowledged the significance of her environment and upbringing in her work. She often cited the formative memory of hearing the deep, mournful singing of a woman named Susan, a caretaker and matriarchal figure in her childhood home. Susan’s earthy, guttural, wordless song stirred Connell’s interest in abstract modes of communication.

Connell made Guardian No. 4 using found and natural materials from around Lake Bistineau, an isolated, swampy waterway on the outskirts of Shreveport, Louisiana, where she lived and worked for the last fifty years of her life. The surface of the piece is overlaid with simplified geometric shapes and rusted metal parts. Its support is a vertical redwood plank covered in a pulpy papier-mâché “skin” made from boiling a mixture of newspaper and glue. The vertical orientation of the work and its skinlike surface lend an anthropomorphic character while also evoking the moss-draped cypress trees that shelter the lake. The pictographs covering the form, however, suggest more multivalent meanings. The abstract images might evoke a female figure, a sentry holding a club, or a prison guard’s key ring. The work’s title indicates protection or guardianship, but who is the guard looking after and what does it protect one from?

Connell acknowledged the significance of her environment and upbringing in her work. She often cited the formative memory of hearing the deep, mournful singing of a woman named Susan, a caretaker and matriarchal figure in her childhood home. Susan’s earthy, guttural, wordless song stirred Connell’s interest in abstract modes of communication.