Skip to main content

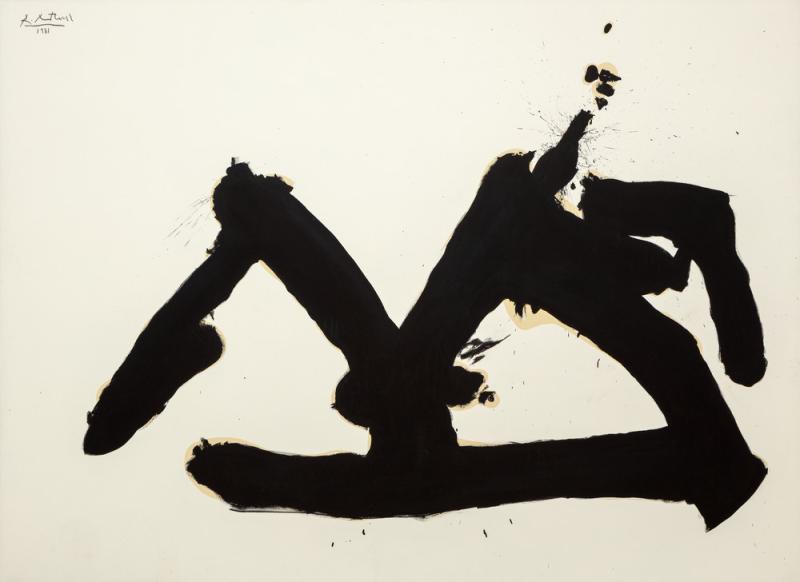

Stephen's Iron Crown

Artist

Robert Motherwell

(American, 1915 - 1991)

Date1981

MediumAcrylic on oil-sized canvas

DimensionsUnframed: 88 x 120 1/8 in. (223.52 x 305.12 cm)

Framed: 89 1/2 x 121 1/2 x 2 1/8 in. (227.33 x 308.61 x 5.4 cm)

Framed: 89 1/2 x 121 1/2 x 2 1/8 in. (227.33 x 308.61 x 5.4 cm)

Credit LineCollection of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Museum purchase, Sid W. Richardson Foundation Endowment Fund

Object number1985.1

Status

Not on viewSignedrecto u.l.c. "R. Motherwell[underlined]/1981"

verso u.l.c., "Stephen's Iron Crown/(Joyce)/R. Motherwell/1981." [verso inscription not verified 11/21/97]

Copyright© 2020 Dedalus Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Category

Label TextThroughout his career, Robert Motherwell worked in series, and often the compositions from one series affected those in another. Stephen’s Iron Crown, 1981, is part of a group of paintings based on a series of oil-on-paper works from 1979 called Drunk with Turpentine, which the artist generated by the process of automatism. Automatism, or automatic writing, is essentially a form of doodling employed to tap into the unconscious. Motherwell thinned oil paint with turpentine to the consistency of ink and spontaneously let the composition arise from the poured medium. The oil bled into the paper, producing a halo effect that appealed to him. For Stephen’s Iron Crown, he used passages of ochre paint along the edges of the black to simulate that look.

The paintings generated from the Drunk with Turpentine works all bear titles referring to the modernist writer James Joyce (1882–1941). Motherwell perceived Joyce’s stream-of-consciousness writing as being akin to automatism. Stephen’s Iron Crown derives its title from a reference in Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) to the iron crown of King Stephen of Hungary. In the year 1000, after Stephen christianized his country, the Pope gave him the crown for his Christmas Day coronation.

Motherwell’s Joyce-inspired images, like his other works that refer to writers (such as Stéphane Mallarmé, Rafael Alberti, and Octavio Paz), present not textual illustrations but visual correspondences to human feelings, expressing Motherwell’s adherence to the Symbolist Mallarmé’s dictum that one must strive to render not the thing itself but the effect it produces.

The paintings generated from the Drunk with Turpentine works all bear titles referring to the modernist writer James Joyce (1882–1941). Motherwell perceived Joyce’s stream-of-consciousness writing as being akin to automatism. Stephen’s Iron Crown derives its title from a reference in Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) to the iron crown of King Stephen of Hungary. In the year 1000, after Stephen christianized his country, the Pope gave him the crown for his Christmas Day coronation.

Motherwell’s Joyce-inspired images, like his other works that refer to writers (such as Stéphane Mallarmé, Rafael Alberti, and Octavio Paz), present not textual illustrations but visual correspondences to human feelings, expressing Motherwell’s adherence to the Symbolist Mallarmé’s dictum that one must strive to render not the thing itself but the effect it produces.